Kunming-Montréal agreement on biodiversity gave us hope, now we must go further

- Yen Parico

- Feb 5, 2023

- 3 min read

One month on from COP15, Yen Parico argues that future ambition on biodiversity protections must place expansion of indigenous rights at its heart

Anja Schwegler

Last December, nearly two hundred nations ratified the Kunming-Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) in Montréal, Canada. Four goals and twenty-three targets were decided to secure nature’s fate.

Set to be the replacement of the Aichi targets, 20 targets set in 2011 to address biodiversity loss, many are still questioning whether the level of ambition touted by participating nations is reflected in the Kunming-Montréal GBF. The Framework is not not perfect. In fact, it’s far from it, but it’s a good blueprint. We can’t afford another setback given the complications and postponements that this COP has already faced. Most importantly, this framework can be used to track progress and hold governments accountable for their obligations.

"Indigenous communities also receive a disproportionately low amount of resources and compensation given the important role they play in the defence of our biosphere."

The negotiations were, however, characterised by walkouts by a group of negotiators from developing countries during a working group session on resource mobilisation that transpired just a few days before the agreement was hammered out at the summit. Why was this such a big deal? The biodiversity financing gap necessary to overcome if we are to continue ‘living in harmony with nature’ ranges between $600 to $820 billion USD per year. Indigenous communities in particular have fallen behind on funding receipts, despite the fact that about eighty percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity is on Indigenous lands. Forty percent of Earth’s remaining high-quality, ecologically intact areas are on Indigenous lands, even though Indigenous communities make up less than five percent of Earth’s population. These communities also receive a disproportionately low amount of resources and compensation given the important role they play in the defence of our biosphere. Luckily, despite the walkout, the final agreement aims to mobilise at least $200 billion USD per year by 2030 – a far cry from many key proposals, but still enough to claim to close the biodiversity funding gap.

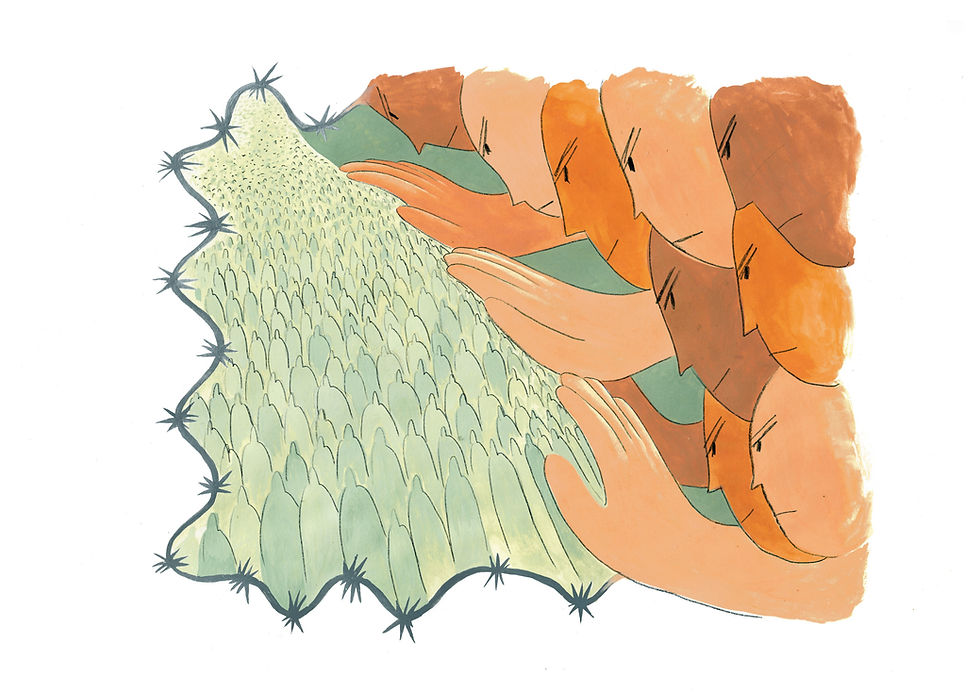

The most contentious target at COP15 was the 30x30 target — which means protecting and conserving 30% of land, inland water and coastal and marine areas by 2030. This has often been accompanied by the narrative of a false assumption that large-scale, area-based conservation is not compatible with the interests of Indigenous peoples and local communities. Narratives like these have unfortunately become commonplace. At COP15, my organization, the Nature Needs Half coalition, advocated for expanding protection and conservation proposals to half of the planet’s lands and seas – doing so largely by strengthening and expanding Indigenous land tenure.

"Even as we enter climate and biodiversity breakdown, only seventeen percent of land is currently protected."

The Tenure Facility states that Indigenous Peoples occupy only twenty percent of the land to which they have claims – meaning justice for Indigenous Peoples cannot merely involve defending current territories. We are facing a situation of land injustice and a crisis of biodiversity.

The position of the Nature Needs Half coalition was that we can solve both.

To start with, Kunming-Montreal’s 30x30 targets fall far below the fifty percent of land and sea which is the global threshold at which we begin to precipitously lose the ecological services upon which we depend, such as carbon storage and oxygen production. Even as we enter climate and biodiversity breakdown, only seventeen percent of land is currently protected. Another seventeen percent is stewarded by Indigenous People and local communities. From this perspective, protections and conservations are already at thirty four percent, exposing the stark lack of ambition of the 30x30 target.

A truly ambitious long-term solution requires putting cultural and human rights at the heart of its framework. The inclusion of ‘free, prior, and informed consent’ rights to Indigenous Peoples in the framework was a promising turning point. However it remains to be seen how this will play out in the implementation phase. A shift in the conservation narrative is necessary, one that places Indigenous Peoples and land practices at the centre of conservation solutions, and not as a barrier to them.

Yen Parico is a representative of the Nature Needs Half Coalition

@yen_parico - IG and Twitter ; @coalitionwild - IG and Twitter

Comments